The Chapel of St Olaf

A drawing of the chapel (as was) by Sydney

Wheeler.

The beeches and oaks that line the western slope of The Carrs are broken at one point by a grove of yew trees. They are the funereal guardians of a sadly neglected remnant of Victorian power and piety: St Olaf's Chapel. To build it, Henry Boddington, J.P. of Pawnall Hall, collected sculptured stones from abandoned churches in the district and asked J Millson to carve the others with birds, animals and the medallion heads of cherubim, the inscription TE DEUM LAUDAMUS (We praise you, God) and the life of dedicatory saint, King Olaf I of Norway.

The west end with the base of the tower and the first three

steps of the spiral staircase.

And this remains

St Olaf's must have been a jewelcase of a chapel with its carvings, chancel, pulpit and spiral stone staircase up to the tower which overlooked the Bollin Valley. Little enough remains. As the yews have grown so has the chapel shrunk, victim of vandals and neglect. Just a couple of courses of stonework remain and the foot of the spiral staircase. It should be noted that, following immemorial convention, its axis is East-West, the rising sun piercing the chancel window.

Carve his name

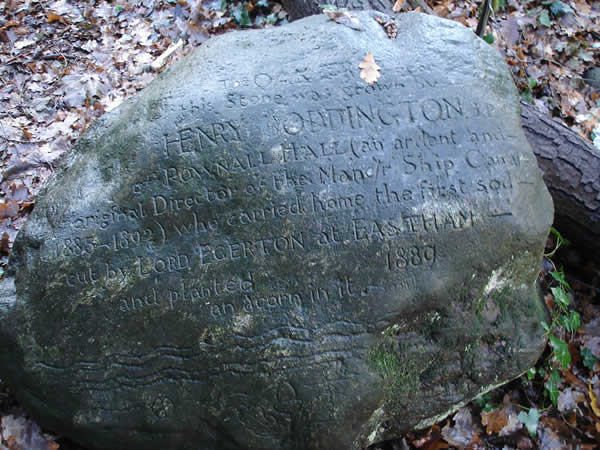

However, not 10 feet away, another monument to Henry Boddington is in rude health. Among the yews that sound the keynote of mortality in this spot stands an oak. Near it lies a broad stone on which we read

"The oak tree near this stone was grown by Henry Boddington, J.P. of Pownall Hall, an ardent and original Director of Manchester Ship Canal 1885-1892 who carried home the first sod cut by Lord Egerton at Eastham in 1889 and planted an acorn in it."

As you can see, unlike the chapel, it has flourished.

The inscription is still, for the most part, legible

What the Hermit said to Olaf Tryggvason

Olaf Tryggvason's early life was that of a Viking raider; he harried the coasts of Northern France and Britain, fought in wars and sea battles and settled nowhere for long. But one day in the Scilly Isles, a hermit told him what would be.

"Thou wilt become a renowned king, and do celebrated deeds. Many men wilt thou bring to faith and baptism, and both to thy own and others' good; and that thou mayst have no doubt of the truth of this answer, listen to these tokens. When thou comest to thy ships many of thy people will conspire against thee, and then a battle will follow in which many of thy men will fall, and thou wilt be wounded almost to death, and carried upon a shield to thy ship; yet after seven days thou shalt be well of thy wounds, and immediately thou shalt let thyself be baptized."

And so it happened. At which, Olaf returned to Norway and became that country's first Christian king (995-1000). He played an important part in the conversion of the Vikings to Christianity and is said to have built the first church in Norway (in 995) and to have founded the city of Trondheim (in 997). Boddington saw him as the ideal warrior, a man of both martial vigour and piety. Different times. The frieze carved by Millson showed Olaf's battles as well as his conversion.

Olaf Tryggvason and England

There is another way of looking at this conversion.

Olaf Tryggvason was the main player in the second wave of Viking raids on England in the late 10th century. England was probably the first nation state, and was so because it was centralised and stable, which meant it was also rich. Tax-gathering was not the hit-and-miss affair that it was in other countries; when the king wanted taxes, he could get them. All of which was very good in its way, except that it had these two consequences: 1) centralised wealth in hard coin was both alluring and easy to 'transfer', and 2) it gave the king another 'weapon' against the invaders.

In 991, Tryggvason led a fleet of 92 ships to raid the coasts of Kent and Essex. The men of those counties gathered to oppose him, but in a great and vicious battle near Maldon, the English force was wiped out and Tryggvason was set free to ravage the country. King Æthelred called on his last weapon, the tax gatherers, and bought off the Northmen with the enormous sum of £10,000.

And that is called paying the Dane-geld;

But we've proved it again and again,

That if once you have paid him the Dane-geld

You never get rid of the Dane.

Unfortunately, Æthelred didn't have the benefit of Kipling's wisdom, which is why he acquired his apt sobriquet and became Æthelred ('good counsel') the Unready (unræd - 'bad counsel'). (It's quite witty in Anglo-Saxon.) Unsurprisingly, in 994, Tryggvason was back (well, wouldn't you?). This time, ravage and slaughter, and he sailed off with a staggering £16,000.

But he didn't come back.

Someone (Æthelred? the hermit?) had whispered into the receptive shell of his ear that he might have a new task and a new title to go with it, that he might become a Christian king and win a boon not to be matched or exceeded by mortal men: a place in the Heavenly Kingdom as the man who converted the northmen.

Now, for the most part, the pagans of eastern and northern Europe had been brought over at the hands of the missionaries, men armed with a staff, scrip and crucifix who were generally slaughtered, but occasionally would escape this fate for long enough to convince a tribal leader to join the side. It was a way blessed by the church and hallowed by the example of the founder and his disciples.

Then there was Olaf Tryggvason's way. It differed only in incidental details from his methods of earning a living: raid, kill, extort. He merely added conversion to the extortion, a booty of gold and souls.

He marched on until the year 1000, when he died as he had lived, fighting. The victor that day was Sweyn Forkbeard, whose son, Canute, would one day rule as the Christian king of England, god-son, so to speak, of St Olaf, who neglected to turn his sword into a ploughshare, but only because he didn't know what a ploughshare was.